Fake news has become an unfortunate part of the media landscape, spreading wildly across computer screens and mobile phones and being shared on every social media platform in existence. And readers are being suckered by these sites every day, convinced that they are reading something real.

Of course, fake news isn’t a new problem for the media.

“In the past, people fabricated content. There were ‘midnight flyers,’ which were pieces of propaganda usually sent out by candidates and put on the windshield of your car or under your door at home. And there were forms of content that contained serious misinformation in them. Sometimes they looked news-like and sometimes they didn’t,” explains Dr. Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. “But there wasn’t a mass distribution system for it, so it had real trouble taking hold. Now with the web, anyone can sit at the computer, create content and try to move it virally through like-minded channels. It doesn’t take any time to do it, and it isn’t expensive.”

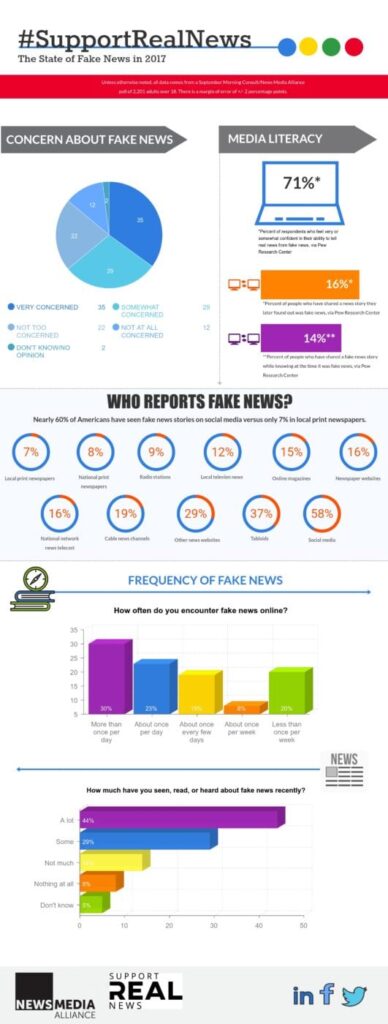

Part of what helps fake news thrive today is the public’s reliance on social media for their information. A poll conducted by Morning Consult for the Alliance in September found that 41 percent of people turn to their social media feeds for the news. That means that Twitter and Facebook, the platforms that have, in some ways, democratized news more than ever before, are allowing the public to be conned every single day by fake news that scrolls across their screens.

The same poll found that 58 percent of people reported they have seen fake news on social media. Even tabloids ranked lower, with only 37 percent of respondents believing they’ve seen fake news via that medium.

But how big of a problem is fake news, quantifiably speaking?

First, we have to define fake news.

“I think ‘fake news’ to most people means ‘something I don’t like.’ When Donald Trump says ‘fake news,’ it means ‘I don’t like it. I disapprove of it. I think it’s unfair or false,’” says Jamieson, who is also one of the founders of FactCheck.org. “So the term is imprecisely defined.”

The Alliance operates with the definition from the Stanford University report “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election” by Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow, which defines fake news as “news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false, and could mislead readers.”

According to the Morning Consult poll, 44 percent of people have heard a lot about fake news recently, while 29 percent have heard some about the problem. Meanwhile, only 35 percent of respondents were very concerned about fake news, and 29 percent were somewhat concerned. At a time when the phrase “fake news” seems to pop up in people’s news feeds at least once per day, conservatively speaking, anything less than 100 percent concern from the public is troubling.

Part of what we believe is affecting this number is trust in the news. An August poll by YouGov/The Economist found that 27 percent of respondents believe that “mainstream” media report fake news most of the time. Meanwhile, a YouGov/The Economist poll from February found that 24 percent of people think the news media is unfriendly to the American people, while another 18 percent said outright that the media is an enemy of the people, further explaining the lower-than-expected concern over fake news — if you view most news as fake news, you’re unlikely to believe that the media environment can be fixed.

Once you take into account people’s views of fake news, you then have to look at how people are being fed fake news stories. The Morning Consult study found that 53 percent of people are seeing fake news online once per day or more, and 79 percent of people have, at least once, started to read a story before realizing that it was fake news. So where are they encountering these articles? A large percentage of them are getting their fake news from social media.

While real news sites see only about 10 percent of their traffic coming in from social media, according to the Stanford report, fake news sites get nearly 42 percent of their traffic from social media links. Because standard news sites are easy to visit through direct browsing, and are also categorized by search engines as news. Real news is served to people on their smartphones, via podcasts, in headlines on Google and other search sites, not to mention through traditional means such as television, print newspapers and the radio. Fake news, on the other hand, is unlikely to be part of a person’s intentional news diet. The sites are not treated the same by search engines, and your news app won’t be sending you alerts when fake news articles are published. The easiest way, then, for someone to encounter fake news is through shares from friends or other like-minded individuals.

Another reason fake news has taken hold is that most people believe they can tell the difference between fake and real. A whopping 71 percent of respondents feel somewhat or very confident that they can tell fake news from real news. And yet, in a December 2016 poll from the Pew Research Center, 64 percent of U.S. adults said that fake news was causing a great deal of confusion about current events.

Part of that, Jamieson believes, is because of confirmation bias, which leads us to believe those things that we agree with.

“Human beings are likely to be uncritical of things that are consistent with their ideology, and we now have a means of transmitting content to other people who agree with us by just clicking the ‘send’ button. And when somebody we trust sends us something, we’re likely to accept it as believable because they’ve certified it,” Jamieson says. “So we’re all vulnerable because humans have confirmation bias.”

A YouGov poll found that 72 percent of people believe stories shared by friends on Facebook at least a little. A story from a source that a person doesn’t know or trust, then, is less likely to be trusted right off the bat.

However, people also willingly share fake news, with the Pew study finding that 14 percent of people have shared a story they knew at the time was fake news, and another 16 percent saying they shared a story they later found out was false. So while news consumers believe they can tell the difference, anecdotal evidence as well as polling suggest that there’s still a gap between perceived and actual media literacy.

So, how can the news industry combat this problem if the people don’t believe it’s a real issue?

Local news is the most trusted, with only 7 percent of Morning Consult respondents believing their local newspaper has ever reported a fake news story. National newspapers are close behind, with only 8 percent believing they’ve reported fake news. Newspaper websites, on the other hand, were less trusted, with 16 percent of respondents saying they’ve read fake news on a real newspaper website.

Considering the bias people perceive the media to have, it’s also important that news outlets make a concerted effort to better distinguish between editorial and news, to lessen the confusion and ensure that people are not mistaking op-eds as biased news, especially online, where there is less obvious demarcation.

You can learn more about how to promote better media literacy from Alliance CEO David Chavern and from our ongoing #SupportRealNews campaign.

You can also use and share our infographic on fake news:

Jennifer Peters is former content manager of the News Media Alliance.